So I think I mentioned yesterday that via ferratas used to be graded from 1 to 5. There are actually multiple grading systems in existence. The one that’s popularly used in English speaking countries is the one invented by guide book writer Cicerone, and since adopted by the Rockfax guides. The way it started out was each route would have a numeric grade from 1 to 5, and an alphanumeric grade from A to C.

The numeric grade describes the technically difficulty of the VF. From Cicerone, “Via Ferratas of the Italian Dolomites, Volume 1”:

- Easy routes with limited climbing, suitable for the young and inexperienced. They require a head for heights and sure-footedness.

- Straightforward routes for the experienced mountain walker or scrambler with a head for heights.

- Rather more difficult routes, not recommended for the novice. Complete freedom for vertigo, sure-footedness and competence with the use of self belay equipment needed.

- Demanding routes, steep rock faces requiring a fairly high standard of technical climbing ability.

- Routes of the highest technical standard and suitable only for the most experienced ferratist.

Then there’s the alphabetic grade, which describes the seriousness of the mountain conditions. A is straightforward outings in unthreatening terrain, B requires a degree of mountain experience, C requires experienced mountaineering skills and a mishap could have “the most serious consequences”.

To put this into context, VF Brigata Tridentina, which we did as our warm up, is graded 3B. That’s pretty much the definition of “generic, middle of the road via ferrata”. Vf Sci Club 18, which beat us up, is a 5B. VF Punta Anna, which we wanted to do on Sunday but bailed due to the weather, is a 5C. The one we pottered around the waterfalls on is a 1A.

This all worked fine.

Then someone built VF I Magnifici Quatro (The Magnificent Four)

VF I Magnifici Quatro (from here on, “M4”) is graded 6B. They literally had to invent a new grade for this bugger because 5 really didn’t cut it. It might give you the idea that it was as “easy” as the Sci Club (briefly the most technically difficult VF in the high Dolomites), and that would never do.

M4 is quite literally in a category of its own. My uncharitable description of it, after doing it today, is “a brutal via ferrata in a hole that alternates between being dusty and muddy and which keeps trying to kill you”.

Sylvia and I did it in 2013, when we were at the top of our climbing game, and we aced it. Today went less well, but we were OK.

It’s appropriate to explain where the name comes from. 4 mountain rescuers went out on Boxing Day in 2009 and never returned. These heroic individuals were killed in an avalanche. The via ferrata was built in their memory.

It was built to be, without question, the single most technically difficult ferrata in the high Dolomites, probably the most technically difficult one in Italy, and one of the hardest in the world (the Austrians have a ludicrous one called VF Adrenaline).

It does not disappoint.

You are advised to take a rope with you. We did, in case we needed to retreat by abseil, use it to assist ourselves, or potentially rescue someone else who’s got stuck. My pack was heavy via 30 metre rope and some extra bits of metal to use it effectively though.

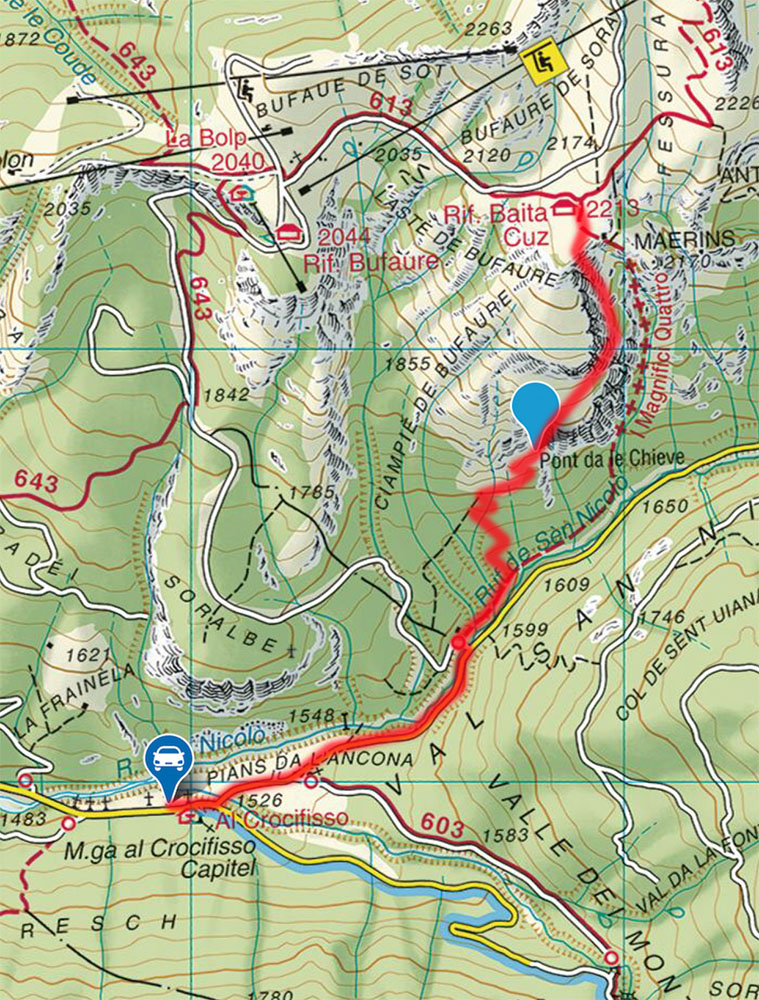

Here’s the overview:

The first thing that should be noted is that the ferrata is not where the map says it is. The markers were added by me to the app in 2013 because at that point, it hadn’t appeared on the maps yet. Now it has, but it’s in the wrong place.

You’ll also notice there’s no descent route marked. That’s because we cheated. More on that later.

Lengthy drive from Corvara, into the Val di Fassa, which is on the opposite corner of the Sella Group: the roundabout of the Dolomites. This meant having to go over two passes, including using the highest paved road in the Dolomites, at Passo Pordoi.

A descent of Pordoi took us to the busy town of Canazei, where they have police officers standing in the middle of Zebra crossings, directing traffic and vastly increasing the chance someone (them) will get hit. Have to say, I prefer Corvara, which is more centrally located and isn’t heaving all the time. I also had a bad experience with a hotelier who seemed to be the Italian version of Basil Fawlty there many years ago, and I’ve gone off the place ever since.

A short drive down the Val di Fassa takes us to the pretty town of Pozza di Fassa, where we turn left and start the drive up the side valley of S. Nicolo. After ascending about 200m from Pozza, we park at a chapel and start walking.

A side path soon appears by a small wooden hut, which has a nice carved wooden sign on it announcing the Ferrata, with a faded note underneath where I could just about read the English words, “Extremely difficult”.

The approach now becomes a pleasant woodland path (the entire ferrata is below the tree line) which gets steeper and steeper and ends up being reminiscent of the punishing approach to Sci Club 18, with a series of short, steep switchbacks which bring you closer to the cliff face, metre by agonising metre, but never seem to actually get you there. At least it’s in pretty pine woods though: it smells lovey and we can admire the wildlife.

Then suddenly we enter a huge cleft in the rock, that goes up fro about a hundred metres and overhangs at the top. The soil gives way to rocks, covered in dust, which turns to mud where water is seeping out of the mountain side. M4 is many things, but a climb on a cliff face with stunning views it’s not. You do most of your climbing in big dusty/muddy holes.

It’s time to gear up and get going. It immediately throws a slight overhang at us, which relies on powerful cable hauling. Get used to this, as it’s going to become a theme.

After that it becomes less steep, but awkward for a few metres, and then suddenly there’s this nasty thrutchy move across a crevice onto another slightly overhanging cliff face with a big loop of wire stuck into it. Your mission, should you decide to accept it, is to get your foot into the wire.

By this point the climber will notice the unusual protection. Sci Club 18 innovated with rubber bumpers on the pegs (OK, it wasn’t quite the first, but they were new at the time). M4 has a couple of other innovations. Many of the pegs terminate in almost closed hooks which you can thread your rope through if you want to belay a following climber. You could probably even use these to pitch it as a sport aid climb, although I’ve never heard of anyone trying this.

The other innovation is that the pegs, instead of being straight, curve down at the end and run parallel to the cable for a few centimetres. This is presumably to avoid impaling yourself on the open end of one if you fall, and seems like a clever idea, but as I discovered later, there’s a problem with these.

Anyway, after getting my foot in the cable, I climbed a few very awkward and very steep sections, where the ferrata couldn’t make its mind up which side of the cable I was supposed to be on. This is poor design, frankly. This is followed by an airy traverse where I have to trust the cable as I haul myself over the void. After this, we both find ourselves in the first of M4’s 2 big set pieces:

The Grande Dom

I assume it means “big dome”, but the other interpretation is valid because M4 is about to beat the shit out of you. Here’s how this works: you step up awkwardly onto a stemple under a slight overhang, smack your head on the rock above you (thank goodness for helmets), wiggle about in the crack, and then you are confronted with the crux of the whole ferrata.

I mentioned the Cicerone/Rockfax grading system. There’s another popular one, mainly used in Germany, which grades each section of cable on a Ferrata from A to E. The ferrata then gets the technical grade of its highest section:

A is “easy” – walking, basically.

B is “moderate” – scrambling, exposure.

C is “difficult” – climbing up to vertical, some small overhangs.

D is “very difficult” – long sections of vertical rock, proper climbing technique needed.

That’s where pretty much every via ferrata in the high Dolomites stops. Sci Club 18, which gave us a good kicking a few days earlier, has precisely 2 D sections along its entire 400m length. There are lots of C/D sections.

Sci Club 18 is a very hard ferrata.

Just to get here, we’ve already done 3 D sections. Now here’s the grading for each cable section in the Grande Dom: D E E D D C/D.

Yes, there’s a grade E. It is described thus:

E is “extremely difficult” – at a bare minimum, vertical rock with no stemples. Severe overhangs. Considerable power and training required.

And M4 is about to throw 2 of them at us, consecutively.

So yeah, we’ve just done the D. The 2 Es are short, but extremely strenuous severe overhangs with just cable (no stemples). I hauled my way up the first and then managed to heel hook the cable to clip. Now I have the second E section to do. I figure the sensible thing to do is try and clip as quickly as possible, to protect myself (unlike sport climbing, you want to clip early when ascending a ferrata).

This was a mistake. Rather than taking my time to see if I can get purchase on the steeply overhanging rock, I lift the leg that was standing on it already and push off the peg that the other one is heel hooked by. This thrusts my body out into space towards the next cable section (a mere D). I am now horizontal in space, one foot on the cable, hanging from it by both arms. I take one arm off the cable to clip. I am now hanging by one arm, but I have clipped. I try to make the second clip, but my arm is getting tired and I can’t reach. It occurs to me that I may be about to fall. I’m already below the cable, and it probably won’t even deploy my screamer, but it the thought still lights up a primitive bit of my brain and I have to fight to keep the fear at bay.

Dangling from a steel cable. I’m sure I’ve seen this in movies. Note my feet are in contact with air and nothing else.

I let out a roar and heave on the arm holding the cable, pushing with my leg and stiffening my core. I make the second clip. I return to having two hands on the cable.

I’m still horizontal. I figure the only thing I can do is cut loose with my feet and hang my entire body, in the void, from the cable. When I do this I will have a few seconds to find a foothold. The rock isn’t great for them.

I cut loose and swing out to the right. I look at the overhanging limestone in front of me, pick out a couple of small footholds as quickly as I can, and put my toes on them. I am safe, but I am experiencing a huge adrenaline surge and I have just scared myself silly.

I didn’t make such a hash of this when I climbed in in 2013, but in 2013 I was in my 30s and was at the top of my climbing game. Today I am rusty and it shows. Today M4 taught me a lesson.

Sylvia wants me to wait for her. The rock is still overhanging, and there’s now a 20-30 metre long overhanging ascending high wire traverse (Zoe is probably reading this and having heart palpitations). I deploy my resting carabiner, awkwardly because my hands are shaking, and clip it to the cable. I now have to make my hindbrain believe that it’s perfectly safe to let go and sit there in my climbing harness, dangling from a piece of dyneema the size of a hair ribbon. My hind brain doesn’t quite believe it, so I keep putting an arm over the cable too. Tomorrow there will be a bruise there.

Sylvia arrives at the 2 E sections. She takes her time and does it in much better style than I did, but the second clip is still hard for her and I reach out and help. Now we have two D sections on the high wire traverse, followed by a climb out of the Grande Dom and the ordeal will be over for the time being.

I make the traverse. My arm muscles are pumped and I’m still trembling. I start to climb out on the vertical C/D section that I remember I still needed to use proper climbing technique for 4 years ago.

And it’s here I discover the problem with the new fangled pegs. Again, I’m clipping early to be as safe as I can, and I clip the cable just above where it connects to the peg and start upwards. It’s then that I realise that I have clipped both the cable and the peg. I try to reach down to free it, but I can’t reach. Time to evaluate my options: I can try to downclimb: it’s an overhang below me and the odds I will fall and deploy my screamer are very high. I can extend the sling of my resting carabiner, clip it to the peg above me, weight it, literally turn upside down in space and free it. That does not appeal.

I could try to get my rope out and abseil down a metre or two to free it. That appeals about as much as the whole “upside down” thing.

In the end I ask Sylvia if she can come and free it for me. I then find some purchase on the rock, above my protection and aware that a fall would hurt, and stay very still.

Sylvia arrives and frees the carabiner. I climb out, grabbing the same tree root I grabbed in 2013, and haul myself onto the flat expanse of grass in front of me. The Grande Dom is over. Time to take my helmet off and try to compose myself after what was very much not the best piece of via ferrataing I’ve ever done.

We’re now on a broad and verdant ledge, about half way up the cliff. The ferrata turns into a path, sometimes cabled (mostly to show the direction to go, but sometimes to help over slippery and exposed ground) leading through the woods. Since the ferrata was built the soil erosion here has got very bad in places, and I imagine it would be a quagmire after heavy rain. With the dirty, dusty rock and all the mud everywhere I wonder how long this VF will remain viable. The path follows the cliff edge and eventually leads up through a bank of stinging nettles(!) until you enter another big cleft in the rock. This is:

The Grande Camino

M4 is very much a via ferrata in two acts. This is the second. It also has a short prologue and epilogue, but the meat is in the previous section, and this one. It’s almost a Venus and Mars thing; the Grande Dom is characterised by the sort of powerful steeply overhanging climbing that young muscular men seem to excel at. The Grande Camino is a 100ish metre high slab that starts off vertical and gets shallower and shallower as you climb, until you end up walking. It requires thoughtful delicate footwork and balance, and is generally the sort of climbing that women excel at. The cable is cleverly placed to give you lots to think about with some quite delicate and run out sections. Frankly I could do this sort of climbing all day; it appeals to the tactician in me. No matter how much finesse you apply to the Grande Dom (in my case, not much), it’s always going to require some brute strength. This sort of climbing is cerebral, and I love it.

Eventually the angle gets shallow enough to stand up and walk, and then the cable gives way to a wooded path again. This time it’s very short, leading to M4’s Headwall. This is its last hurrah, and it’s even optional: there’s a path round. If you take it though you will miss out on signing the log book, which is to be found in an alcove halfway up the short headwall climb.

And suddenly, its over. I emerge panting into a grassy meadow with a family standing there watching me climb out over the cliff edge and collapse on the grass, exhausted. The children seem confused. The father explains. “Molto difficile”, I add, by way of an explanation.

Sylvia arrives shortly after me. We exchange a high five and collapse into the nearby refugio, where we immediately order beer.

And that’s it! Very much a “Type II Fun” experience. Sylvia and I have now done the undisputed most technically difficult via ferrata in the high Dolomites, and one of the hardest in the world, twice. Not sure I ever want to do it again (unlike the Sci Club).

Oh, there is one more thing. I noted I hadn’t marked the descent route on the map. Last time we did this we used the official one. It’s a long trudge down a very steep ski slope (somehow you gain about 700 metres doing this ferrata, but I’m not sure where), and it’s horrible. Too steep to walk on, no proper path, slippy grass, hard on the knees.

We went and paid the nice man and used his gizmo to take us into Pozza, then caught a little shuttle bus thing back to the car park. Much more civilised.