All the other via ferratas we’ve done while here have been ones we’ve done before. This one has been on my “to-do” list for some time.

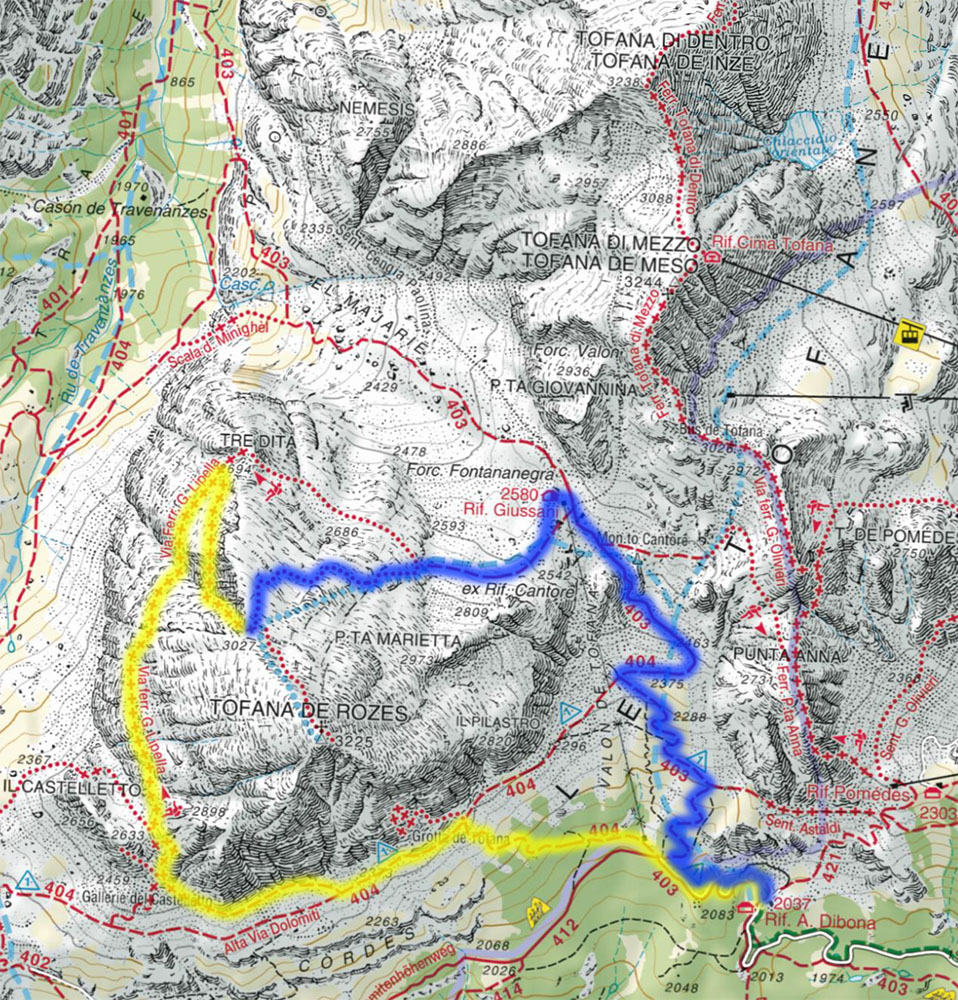

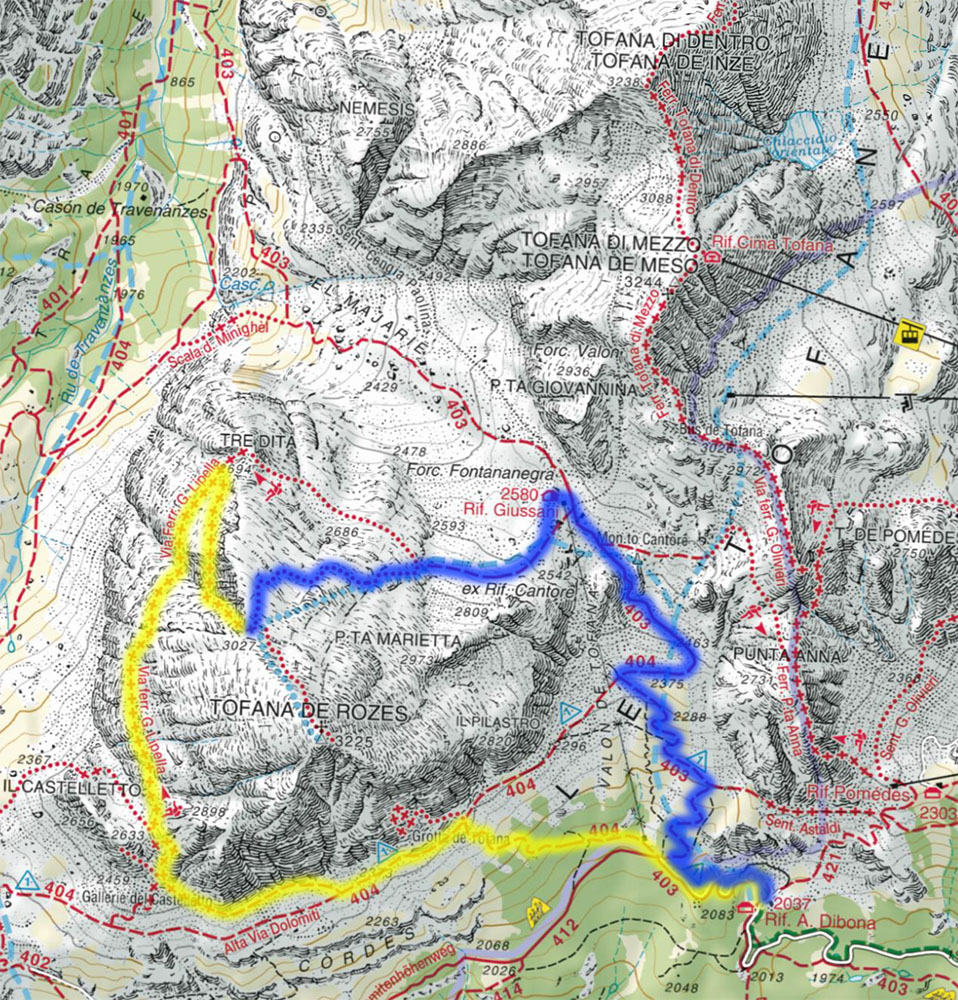

Ascent in yellow, descent in blue. No cable cars or ski lifts to help this time.

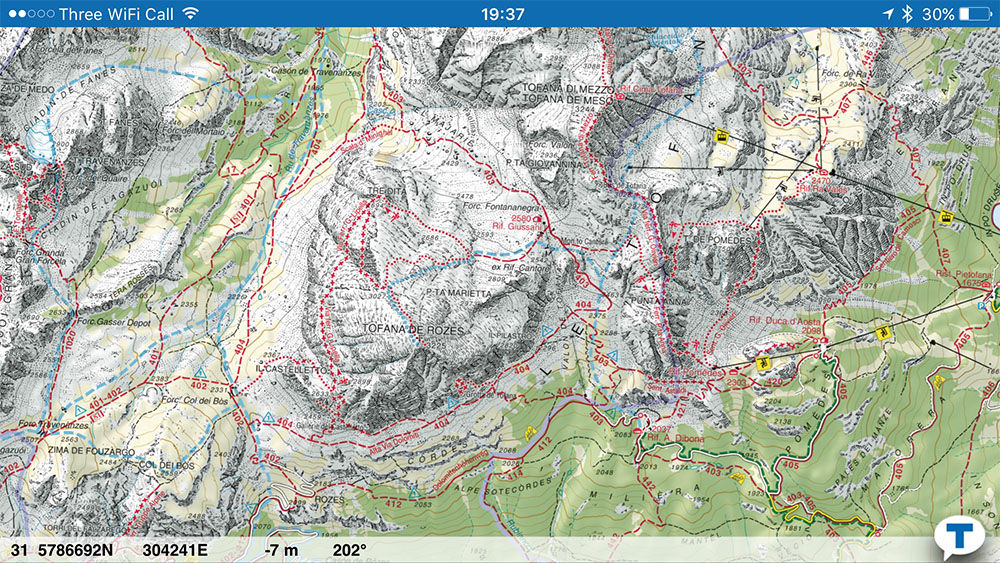

The Tofana group has three main peaks: Tofana di Mezzo, the highest at 3244 metres; Tofana di Dentro, connected to Mezzo by a high ridge and 6 metres shorter at 3238 metres, and Tofana de Roses, 19 metres shorter than Mezzo at 3225 metres and very much the odd one out.

Unlike Mezzo and Dentro, which can be accessed from each other with only a couple of hundred metres descent, Roses is separated from the other two by the pass of Vallon di Tofana, which runs north/south between Mezzo and Roses and forms a 900 metre deep cleft between them. That almost makes Roses feel like an entirely separate mountain.

The vast bulk of Tofana de Roses, busy making weather, seen from near Rifugio Dibona

It’s also very different in character. Mezzo and Dentro, together with Mezzo’s southern ridge, Punta Anna, rise out of the lower slopes of the massif as a thin ridge. Side-on from Cortina, they present a massive wall, soaring 2 kilometres above the town. From the south, they almost disappear as they merge into a narrow ridge.

Roses is different; it is a vast hulking presence of a mountain which, together with its massive scree-covered lower slopes utterly dominates the Cortina side of the Falzarego pass. Even though it’s shorter than the other two (just), it demands your attention. It makes its own weather, distinct from the other two, and seems to just sit there as if to say, “I AM A HUGE MOUNTAIN, LOOK HOW IMPOSSIBLY BIG I AM!” If you’ve seen Snowdon, this thing is the size of three Snowdons stacked on top of each other (from sea level). Even from its base near Cortina, it’s still 2 of them on top of each other. This is a big mountain.

And unlike the other two, there’s no cable car or ski lift to help access it. There are ways to the top of lower slopes by either walking down from the Mount Lagazuoi cable car, or taking the ski lift up the lower slopes of Tofana di Mezzo and contouring under Punta Anna using Sentiero Astaldi, as we did last week, but if you want to get up there, and down again, you have to do it all yourself.

With this in mind, we drove down from Passo Falzarego, underneath Mount Lagazuoi, where the Austrian troops used to rain down artillery on the Italian forward position at 5 Torri below in the 1st World War (and where the Italians spent years tunnelling up from below to blow the top off the mountain – the Austrians heard them coming and moved. You can now climb or descend Mount Lagazuoi in the tunnels they built), and turned left onto a single track road that led up to Rifugio Dibona, the highest you can get by car. After a while this turned to a gravel track and in places I had to slow right down to avoid grounding. I’m really glad they gave me a hybrid: in the absence of 4 wheel drive, electric traction is really good at this.

Sylvia on the increasingly narrow approach path 400 metres above the car park.

From Dibona we set out uphill, needing to gain 450 metres to reach the start of the route. We’re both getting very fit now (Sylvia and I have both dropped a dress size in the last week: our trousers keep falling down), and we steamed up here passing walkers and other climbers as we went. This generated loads of heat and we were sweating profusely by the time we passed the caves we’d explored on our day off last week.

The pine-scented path of the lower slopes gave way to scree as we reached the base of the mountain proper, and the path became narrower and more precarious.

Ruins of WWI barracks at the entrance to the tunnels and the start of the ferrata

Eventually we passed an obvious world war 1 observation point, carved into the side of the mountain, and round the corner came upon the ruins of wooden ladders used to reach tunnels that the Italian army had dug into Roses western flank, presumably to try and see what the Austrians were doing on Lagazuoi.

The ferrata starts by climbing through these old World War 1 tunnels. The tunnels are accessed via stemples placed in the rock by what’s left of the original wooden ladders, now over a century old, and enters via the ruins of a small hut, nestled into a rock crevice where the Austrian troops wouldn’t be able to see it (if they managed to spot what the Italians were doing, one well aimed artillery shell and it would all be over).

We entered the tunnels and started to climb, inside the mountain. I remember reading The Two Towers as a kid and finding the Moria passages deeply evocative. These guys did it for real, several times. The tunnels here aren’t as extensive as the Lagazuoi tunnels (there’s miles of those), but there are still the remains of entire barracks and command rooms they dug out of the solid, unyielding limestone in what must have been appalling conditions. Even in later July it was cold. The tunnels were cramped and steep, and while the lower sections have a modern steel staircase installed, the upper sections do not.

Inside the tunnels, lit only by our helmet torches. Turn them off and it’s inky black.

We spent some time looking at the ruins, and expressing our mutual horror at what those young men must have gone through a century ago. It truly defies imagination. World War 1 is still a big deal around here: there are extensive ruins and, with the trenches hewn out of solid limestone and still here it seems to have left a lasting trauma to match the lasting impression it left on the landscape (they blew the top off a mountain!)

The tunnels are steep and we gained over 200 metres inside them alone. In places we had to duck, and apart from the occasional glimpses of daylight where small observation slots were dug (these were dangerous: the Austrians were looking for them), the tunnels were utterly devoid of light, save that provided by our helmet torches. At one point the tunnel crosses an obvious fault line and the roof has been propped up by thick wooden supports to prevent a cave-ins. This ferrata will get you if you’re scared of heights or enclosed spaces, and is not a climb for the nervous!

After about 20 minutes we emerged, blinking, into daylight, and I was able to turn my Fuji X100 camera back from 6400 ISO to 200 ISO and set it for “sunny 16” exposure again. There’s now a bit of a down climb on some ageing via ferrata cable to meet the alternate approach route from the Mount Lagazuoi direction, which avoids the tunnels. There’s been an extensive modernisation effort over the last few years on all the via ferratas in the High Dolomites and there are precious few sections of older style protection left. This pleases me, because the newer stuff is of a much better design. The old stuff survives in tiny patches like here. The rest of this route is in the new (safer) style.

The end of the tunnels. Who turned on the lights? This presumably afforded a good view of the Austrian guns.

The short down climb leads you to a broad ledge. It leads north along the western face of Roses for about 500 metres, getting slowly narrower as it does. There is nothing, yet, to trouble anyone with even the slightest tolerance of heights, but that will come. A few hundred metres in front of us, we spotted two more groups, one large and one small.

Eventually you come to the cable. If you’ve opted for the approach that bypasses the tunnel, this is the first time you’ll need your VF kit, and so it was that the smaller group was stopped here, in the latter stages of gearing up. It seemed to be a married couple, and the man was giving us death stares as we made for the cable in front of him, while he rushed to do up his harness.

I guess he resented the idea that we would “queue jump” and slow him down. I got on cable first and started to climb. Sylvia followed, and the man, his irritation leaking from him, tried to make a point by catching Sylvia up.

Well he tried to. The thing is, we’re both bloody good at this, and other things being equal, we beat guidebook time on cable sections. This is a Cicerone Grade 4C ferrata, so you get people on it who would be scared off a 5 or 6. We do 5s and 6s, so this is our bread and butter. We left them both in the dust while he presumably seethed at being “chicked”. Chalk one up for the women.

Sylvia on one of the protected ledge sections. She’s stepping over a rock crevice that’s … well, who cares how deep it is after the 1st 100 metres? It’s deep.

The character of this route soon became apparent. It heads north, along the west face. It follows a ledge for some time, then climbs up to the next ledge, and repeats. The climbs are always cabled. The ledges sometimes are and sometimes aren’t. The guidebooks all describe this as seemingly never ending, and it’s certainly true that you get a lot of cable for your money (er, entry to these is free – ed). This suits me fine: gaining height on a via ferrata cable is far faster and more energy efficient than doing it by walking.

One of the unprotected ledges. There are a lot of these, and some are narrower than this. Caveat emptor.

This is, however, not a route for those scared of heights. It’s already done claustrophobia with the tunnels. Now it’s going to throw acrophobia at you.

It’s actually nowhere near as exposed as the Punta Anna route that we did 2 days prior, but paradoxically the vast scale of Tofana de Roses makes it easier to capture the vertigo in photographs. A few years ago I’d reached the point where I could handle exposure as long as I was on cable, but cried at short un-cabled sections. If I’d done this route a few years ago, I fear I would have had some sort of acute mental health crisis (not joking). Don’t do this route (or Punta Anna) if you can’t cope with unprotected exposure. Seriously, just don’t – it could literally frighten you to death.

After a few repetitions of the “walk along ledge, climb to next one, repeat” cycle, we caught up with the large group we’d seen earlier. Turns out there were 7 of them, and they followed the usual pattern of having the most able climber at the front, the slowest and most nervous member in the middle, and a spotter bringing up the rear to help.

It’s good etiquette to let faster groups pass you where possible, especially on long routes like this (and on Punta Anna, where you’re racing to get the cable car down, it’s downright rude not to). I’ve noticed a dynamic that seems to happen in these situations, and this was no exception.

You come up behind the spotter and stop, one cable length back. The spotter is helping the slow member with a difficult climbing section. They then move up. You follow, passing the difficult section at speed. The spotter then realises you’re faster than their group and offers to let you pass.

The group we’d just overtaken, on the next ledge section as we moved away from them.

This is what happened here. I thanked her and unclipped from the cable(!) I then went round the bulk of their group, at some speed, using the cable as a handrail but not clipped on to it (I’m perfectly happy to do this on easy climbing sections, but won’t unclip anywhere I feel there’s a danger of me falling)

Zoe has told me, on occasion, that I seem to have an ability to switch gravity off. I guess that’s what I did here as I raced past the group members. I wasn’t showing off, I just wanted to get out of their way, and get on with the climb. Sylvia started to follow me.

Now the second part of the dynamic takes hold: you reach the leader of the group, who is the best climber, and usually a man (this makes me sad – the most impressive ferratist I’ve ever seen was a young woman who overtook me on Magnifici Quatro’s headwall – massive respect due and a privilege to watch that level of skill).

The man will be annoyed, not knowing his spotter invited you to pass the group. He sees himself as the leader and should be the one to make these decisions, but he can’t because he’s at the front. However, since his group is now split in two by the presence of a pair of interlopers in the middle, he has no choice but to let you pass.

So we did, and got on with our day as we increased the distance between us and their group. This was made easier by us not bothering to clip on many of the protected ledge sections, instead using the cable as a handrail, or single clipping, both of which are faster (but obviously less safe: judgement needed) than the full double clip action.

Near the junction, where we had a snack. The drop here is about 700 metres: about 650 more than needed to turn you to a red smear.

Eventually, about 2 and 1/2 hours after we started, a climb section led to a junction as the west face started to turn to become the north face. This is a good point for an escape section, as north faces can be icy, even in summer. The left fork led round the north face to meet up with the main descent path from the summit. The right fork switched back above our previous route and continued the ferrata. We stopped here and had some chocolate and dried fruit before turning right and continuing on.

The unprotected ledge leading to the massive bowl. Note there are 2 other climbers in this photo (click to enlarge). Looks like they overtook the big group too.

At this point we were at 2700 metres and had been gaining height much more rapidly than on this ferrata’s “sister route” of Punta Anna, two days prior. This was about to have consequences. The route continued on an entirely unprotected high ledge for some time, round into a massive scree bowl below the summit. Although we’d turned away from the north face proper at the junction, the curvature of the bowl created another north face here, and there were a lot of little meltwater waterfalls from the recent snow doing their best to drench us as we started to climb steeply upwards on the final, but very long cable section.

Climbing in the big bowl. At the bottom left you can just see the group we overtook earlier.

That’s when it hit us. Somewhere around 2800 metres I started to feel light headed, almost drunk. Sylvia was struggling on the more powerful moves too. We were both short of breath, and recognised what might be the initial signs of acute mountain sickness (AKA altitude sickness).

This confused us. We’d gone to over 3200 metres on Tofana di Mezzo 2 days prior and, while a little short of breath, were basically fine. Yet here we were both developing symptoms (albeit mild – if they were serious we’d have attempted to downclimb) 400 metres lower than that. Given our proximity to the end of the ferrata, which stops at 3000 metres, 200 below the summit, we decided to carry on climbing and reevaluate at the end of the cable.

As we approached, our symptoms started to ease and we developed a theory as to why this had happened. On VF Punta Anna, most of the strenuous hard work is lower down, between 2500 and 2700 metres. The climbing on Punta Anna is technical, slow and difficult and you have a decently long walk along the flat top of Punta Anna around 2700 metres before starting to climb, gradually, again.

This gives time to acclimatise. Lipella, despite seeming to go on forever, is actually a shorter ferrata and gains height quickly and relentlessly. The climbing out of the bowl, while technically easier, is still strenuous. It throws the altitude at you more quickly, and makes you work hard while doing it.

End of the ferrata and, 200 metres above us, the summit.

As a result, our metabolisms took a little time to catch up. Once they did, we were fine.

Suddenly we rounded a corner and the summit appeared in front of us. A couple of minutes later and the ferrata ended at a plaque commemorating the life of Giovanni Lipella, the mountain guide after whom the route is named.

The way to the summit was now clear, but the mountain here is shaped like an aerofoil and it was taking the prevailing wind and accelerating it hard over the ridgeline, where at least part of the path went. The clouds were being squeezed over the summit itself and sped up so they looked like one of those time lapses, only in real time. The wind was howling, yet if we moved 5 paces onto the other side of the ridge, it stopped completely. Aerodynamics is weird.

There were a couple of groups up there, having conversations, apparently about the wisdom of going to a point summit where the wind could literally pick them up and suck them into oblivion. Time was getting on, we still had a long walk down back to the car, and frankly the wind was bothersome. Given we’d already summited Tofana’s main peak 2 days earlier, had completed the ferrata, and had made it to the psychologically important 3000 metre mark (and climbed more than a thousand metres from the car), we decided to head down the descent path.

More importantly, unusually for a Dolomite summit, there was nowhere to buy beer up here.

Amazing view of Tofana di Dentro (left) and Tofana di Mezzo (right) from the descent path.

“Path” is a bit optimistic for what this is. The sloping north face is dotted with cairns. How you get between them is up to you. There were quite a few people around, many seemingly having tried to summit by walking up the ferrata’s descent path. Rather them than me; as I said previously, gaining height on cable is much more energy efficient. Walking up, especially on this shifting and annoying north face scree slope, must have been soul destroying and exhausting.

The ruins of Rifugio Cantore

Quite a few of them, while attempting to descend, were literally falling on their arses.

We walked, scree surfed and boulder hopped our way down, passing the walkers who had no inkling of the howling gale they were about to encounter as they turned onto the summit ridge. The view is amazing though. You can see Tofana di Mezzo, the summit of which we’d stood on 2 days prior, Tofana di Dentro, and its terrifyingly named subsidiary peak, Nemesis. The best bit was looking north and east though, where we could literally see for hundreds of kilometres, into Austria and probably into Switzerland. Far, far off in the distance were the 4000+ metre monster alps with their permanently glaciated pyramidal summits. Here we were among the clouds on the roof of Europe, and it was amazing!

Cheers! We normally do this at the summit, but needs must. Also it’s Heineken which is rough compared to the local stuff

The descent proceeded quickly until we came to the pass at the Vallon di Tofana. There we found the ruins of Rifugio Cantore, along with some very well preserved World War 1 ruins which were presumably some kind of forward command post for the Italian troops. Nearby we heard the generator of Rifugio Guissani, situated right in the saddle of the pass, and made our way there for a beer. We were now half way down our kilometre descent.

Beer finished, we continued down a path that quickly turned into a very easy 4 wheel drive accessible track that allowed us to lose altitude rapidly without too much stress on our poor middle aged knees.

Pretty soon we passed the junction with Sentiero Astaldi, which we’d used to access this part of the mountain several days ago, and not long after the descent path met the ascent path we’d used over 7 hours earlier.

We’d done it! 8 hours round trip (including beer time), a long desired ferrata ticked off the list, and a second vertical kilometre in 3 days. Thoroughly enjoyable, and the scale of the whole thing is amazing.

It’s a very different feel to its sister route on Punta Anna/Tofana di Mezzo. The whole ledges thing is more typical of ferrata routes in the Brenta group, west of the Adige valley and over towards the colossal Mount Ortler (which I’m sure was one of the huge mountains we’d seen from near the summit), and the tunnels give it a lot of variety. I’ll definitely do this one again, but Punta Anna is one I will keep coming back to again and again until I’m physically incapable.